|

| |||||

Earthmanby Maggi Lidchi

|

|

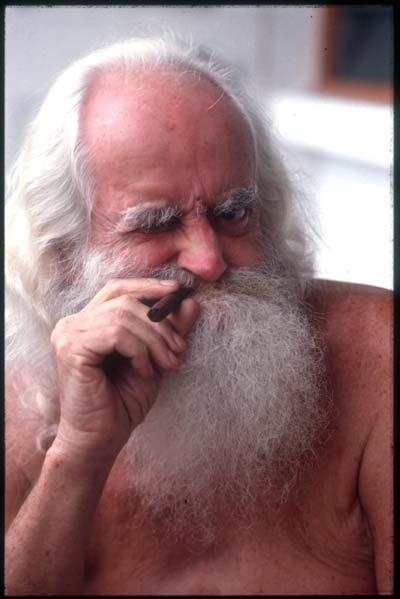

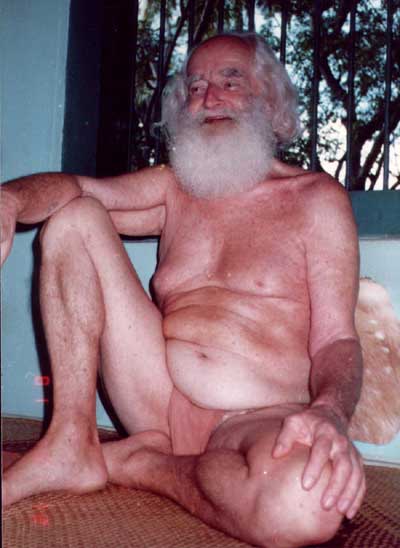

German Swami Gauribāla Giri of Jaffna (1907-84) was, by all accounts, a colorful and enigmatic figure known throughout Sri Lanka for decades. A prominent disciple of Yogaswami of Nallur, his outrageous antics and iconoclastic ways often disguised another side less well known to the public, for he was also an erudite student of the Philosophia Perennis whose theories concerning Sigiriya and Kataragama were decades ahead of the more conventional wisdom of professional academics.

In the mid-1960's Maggi Lidchi of Śrī Aurobindo Ashram met an English seeker who had survived several months of typically severe training under German Swami. His detailed account of his experiences at German Swami's Jaffna ashram Summāsthan formed the basis for her 1967 novel Earthman. "A well regarded novel, praised by Henry Miller and others, of a Westerner's spiritual search in India, his tribulations at the ashram of a Gurdjieff-like Irish swami and continuing series of mystical crises and revelations; likened to Maugham's The Razor's Edge."

Chapters Two through Five of this extraordinarily detailed and acclaimed depiction of German Swami (called 'Irish Swami' in the novel) and his ashram are reproduced here. Download Earthman Chapters 2 to 5 as a single zipped Word file.

Chapter Two

Christopher didn't know who Ayrishswami was or that Jaffna was in the north of Ceylon. He let himself be put on a bus filled with quiet Tamil businessmen going north to the Hindu area on a pilgrimage. He let the bus conductor put him on another bus filled with fishermen coming from the market. For the rest of his life he remembered his continuous gagging at the smell of their empty baskets.

When he got off the bus he had to walk, and was passed from a fisherman to a clerk to a coolie who left him and his case with a servant in a cluster of half-a-dozen houses on the edge of a coconut grove. The servant salāmed him with joined hands and scampered away into the largest hut, the only one with its own garden and kadjan fence. Christopher looked around. The well kept flowerbeds and the neatly swept sand-paths were the first signs of returning order since he had left the Buddhists.

A man was standing at the gate of the main house. He wore glasses, was powerfully built, bare to the waist, dressed like a native. He came towards Christopher with joined palms.

"Good day to you," he said with a British accent. Christopher's eyes went from the flecks of dark pigmentation that dotted the broad fair-skinned shoulders to the abundant copper-coloured hair. This really was an Irishman. He had about him the air of a chief of one of the great clans. He stood looking at Christopher through rimless spectacles. The red hairs on his arms gleamed even in the soothing spent light.

|

|

German Swami Gauribala Giri

(1907-1984) at his ashram Summāsthān in 1981 |

"Are you Irish Swami?" he asked with a stir of something like curiosity.

"I am." He led the way to the entrance of his coconut-thatched house. "You'll find it easier to sit down if you take your shoes off."

Christopher kicked his shoes off, looking into the room, and Irish Swami bent down swiftly to range them neatly together.

Christopher watched the broad freckled back in embarrassment. This man was at least fifteen to twenty years older than he was, but he made Christopher feel worn and used up, untidy. It was the first time anybody had produced a reaction in him in many weeks, and it encumbered him heavily with the almost forgotten sense that he was responsible for how he looked and behaved.

Irish Swami made coffee in silence while Christopher sat on the mat and looked around. There were no chairs, only mats and a table lifted a few inches from the ground by stumpy legs. Apart from this there was a bookshelf. The papers on the table were in neat piles. There was one drawer at the bottom of the bookshelf. Nothing else in which to conceal untidiness. The ceiling was held up by palmyra poles that met the bare beams.

Above that rested a double layer of kadjan thatch. In spite of its bareness the room was marked by a high degree of civilisation. Perhaps it was the predominance of books or the fine quality of the cement or the smell of clean wood and rose petals from freshly spent incense sticks. Whatever it was Christopher felt lumpy and ungainly, as though he and the shabby, bulging suitcase defaced the room. Irish Swami came back from the entrance of the back courtyard where the kerosene stove stood.

He put a cup of coffee in front of Christopher and got himself into a cross-legged position on the floor without using his hands.

Christopher drank the coffee aware of the holes in his socks. He also tried to tuck his feet under himself, managed one but sloshed coffee on to the floor.

"Who are you?" asked the Irishman while Christopher mopped the floor with a grayish handkerchief. The man had a right to some explanation if he were going, for some reason, to take him in.

Christopher explained. He spoke for five hours. Sometimes Irish Swami gave instructions to the servant in Tamil, but otherwise he listened without moving, his eyes lowered.

Christopher had to move. He shifted. He rubbed his ankles. Sometimes he had to stand up and walk about in spite of the holes in the toes of his socks, but he did not stop speaking and eventually he forgot about the holes. He had never had anybody listen to him in just this way-without laughing, sympathizing, showing surprise, delight or fascination. This was passive listening, almost grave, like a steady flame into which he threw everything. Old letters, manuscripts, programmes, anecdotes, souvenirs, trunkfuls of them. He couldn't unload quickly enough.

Three times he thought he had come to the end, but always as he was going to say Well, that's just about all, and once when he had already mid it, he found something else, another vivid fragment that would explain his life.

Finally he muttered in the unsure tone he had started with, "I think that's about it."

The red-haired man lifted his head and looked at Christopher.

"Who are you?" he asked in exactly the same casual, matter-of-fact way he had done hours earlier.

Oh no! Christopher looked around. Was he locked in one of those static illusions again? But he wasn't drunk. And it wasn't static. He could remember the sequence of the day and yesterday and the day before that. It meant that he had been speaking to a nut. He had thought the room and dress were only some sort of eccentricity.

"But I've just been telling you," said Christopher, too discouraged, too tired to play a madman's game. By what dented logic had this man spent hours pretending to listen?

Christopher had come all this way for nothing, and all he wanted to do was sleep. He was too tired to pretend.

"You've told me where you were born and who your parents were and all about your wives and your ambitions and your failures, but who are you?"

Christopher stared into the man's bronze coloured eyes. "Well, that's all I know. I can't tell you more than I know, can I?"

"Ah, then you admit there's a possibility you don't know?"

What sort of man was it who could ask these questions of someone who had been traveling all day and trying verbally to relive his life for hours on end?

"I think I'd better find a bed somewhere and get some sleep," said Christopher wearily.

"There are no beds here. We're free of beds here. Down with the furniture makers." The man pointed a broad thumb at the mat and grinned wryly. It was fast turning into a scene from Alice in Wonderland.

"You're not the Mad Hatter by any chance?" asked Christopher, deciding to sink into the confusion.

"Exactly who I am." A hand covered with first hairs rested approvingly on Christopher's arm. "Come, I'll show you your room. And I'll teach you how to sleep in it." Irish Swami got up in that effortless, unwinding way. "But first we'll get something to eat."

Christopher's welcome of this last suggestion was disproportionate. He had no need for food, his appetite not having returned. However, he had just heard the first unqualifiedly reasonable utterance since his arrival; something which almost anybody might have said in the circumstances.

Irish Swami was sensible about food and served it abundantly and regularly. He was also sensible about sleep once you got used to the idea that the best way to have it was on a thin straw mat. He went to some trouble to show Christopher the adjustment that had to be made so as to sleep on the muscles instead of the bones.

Christopher spent the first few nights tossing on the floor like a banderilla'd bull, and during the day his mind behaved in much the same way under the impact of Irish Swami's conversation, but it was clear that the Buddhists had sent him here on the assumption that he was an eccentric seeker and that the eccentric Swami had taken him into his small ashram for the same reason.

And in a way he was, of course. He was looking for a new exit. Or more positively a tidal wave had washed him up on to Irish Swami's doorstep in this fishing village where the old ways were not viable, and as long as he was here there was no choice but to adapt to certain exigencies. He explained this to Irish Swami to avoid commitment rather than dishonesty, and was told that he had been received for that very reason.

The Buddhist monk had written that he had no preconceptions, no religious background and no particular direction. "Stay three days and then we'll see. The gate is always open if you can't stand it," and after three days, "Stay another week, if you like. The tradition is that an ashram is bound to three days' hospitality to any seeker, no questions. Afterwards things are on a different basis. I'll explain as we go along."

Christopher stayed because he did not know where to go, but also because the unpredictability of this man was the first thing to disperse the numbness that had settled on him since his arrival in Ceylon. It kept him on his toes. Even to be jarred was something, a sign of returning life. For weeks nobody's personality had been important enough to move him out of his inert stupor. Now he was exasperated every time Irish Swami justified his actions by the Tradition. How could a man who constantly quoted Lewis Carroll and Jung and Rabelais and the Vedas live by any tradition without being a false or a nut?

There was only a latrine in the ashram compound, no bathroom, and Irish Swami took him to the well on the fourth morning. The well was very much a centre of the village, where people not only drew their water and bathed but stayed to wash their clothes and exchange news or sit quietly on their haunches while the cotton cloths dried in the sun.

Christopher sat on the paving with Irish Swami. There were only two chain pulleys to lower the buckets: they had to wait their turn. Irish Swami had explained the procedure to him, and for the sake of opaqueness Christopher wore two pairs of underpants beneath his trousers. The men wore loincloths while they endlessly poured buckets of water over themselves, and though Christopher was resigned to this public exhibition he would have preferred to carry a bucket of water back to the ashram as Paul, Irish Swami's Tamil disciple, who lived in the next hut, had been doing for him. But this was the fourth day, and technically Irish Swami was no longer his host but the principal of the ashram initiating him into his way of doing things.

Christopher sat anxious to get it over, though apprehensive of his turn and also interested, despite himself, at this backward plunge in time.

"Why don't you build a bathroom at the ashram?" he asked casually.

"Why should I?"

"I don't know. Isn't it a nuisance to have to go through all this in public all the time?"

"Public?" echoed Irish Swami in his buoyant way as he was beginning to do, to indicate that Christopher was using a term he had himself discarded. "There's nobody but myself and Bhagavan, but if I still have the illusion that it is other people watching me... well, does it matter? We all look very much the same, which is as good a reminder as any."

He held out his arm with its copper-coloured nimbus. "It sometimes happens that I wonder why this isn't brown. It'll happen to you when you've lived in the area a few years." He flicked his forehead and corrected himself. "What am I saying? A few months."

Not bloody likely, thought Christopher. He was acutely conscious of his skin, so much lighter than the Tamil, almost grayish-brown. He did not feel any of the joyous identity with which he had immediately merged himself into Spain or Greece. There was something besides time and space that separated him from these people, and he didn't think it was colour.

"But don't you spend a lot of time just waiting here?"

"Why can't we just sit? What have you got that's so important to do?" Irish Swami rattled off his answers in a new way, which must be the fourth-day manner. The humouring period was up, and though Irish Swami spoke little unless questioned he pounced every time. He always had an answer, immediately and fully formulated, and Christopher saw that by staying he exposed himself to more than a way of living. . . unless he kept quiet.

But when Christopher stood in his two pairs of underpants by the side of the well, while Irish Swami showed him how to latch his bucket on, he forgot. "Why forty buckets? Why not thirty or forty-five?"

For the first time the people were all looking at him. They had been doing so from the beginning but never all at once. It made Christopher nervous and betrayed him into speaking just when he most needed to be silent.

Irish Swami turned away from the well. "He wants to know why forty buckets?" he shouted out in English. "Why not thirty or forty-five?" He repeated it in Tamil.

Christopher, humiliated and angry, retained just enough observation to see that most of the Tamils did not understand. A buzz of discussion went around and someone cried out in English, "We always done like this."

"That's your answer," grinned Irish Swami and went on pulling at the chains. "That's the Tradition."

He made Christopher pull the second bucket up and showed him exactly at what angle to pour it over himself. Not down his back or down his front but directly over himself so that the water caught as much of his body as possible.

"That way forty buckets is just about right to keep you cool for the rest of the day. If you waste it you might need forty-five at that. These people have it pretty carefully worked out. They've been doing it for centuries. Good for your arm muscles anyway."

Irish Swami reverted to his third-day manner to say this. The question to the villagers had been a warning. No humour. For the first time Christopher began to see how this man operated. First a whip-flick for surprise, then once you were going a carrot in the form of intelligent conversation yesterday, then fourth day a kick in the rump to remind you where you were and who was boss.

Christopher worked the pulleys impassively. That explained the subdued condition of Paul and Ramesh, the two resident disciples. And Irish Swami hadn't wasted a minute.

Here he was on the morning of the fourth day, his beer belly hanging over the elastic of his underpants, pouring water over his stupid head for all the world to see, except that it wasn't all the world, only a few dozen, very few, sitting on their haunches.

A few villagers who didn't matter, he told himself. It flustered him that they could all sit for hours in a position that would have felled him in minutes. And they were all lean and hard and covered with a simple strip of loin cloth while he stood at the centre in two pairs of complicated jockey trunks, the fat boy of the class fumbling with the bucket and wasting water... the village idiot.

It was a bad dream. How had he got into this? He tried to think of familiar situations and people to tide him over the last twenty buckets. His arms were already tired. All he could summon was Raoul's face smiling at him with Gallic irony.

"Twenty-five!" sang out Irish Swami. He was calling the score every five buckets. This sort of strategy might work very well with the passive, disciplined Tamils and even with the wilder but more lethargic Sinhalese, but it certainly wouldn't work with Progoff. The gate was there and it was open, as Irish Swami had pointed out, and he was certainly going to use it, but not before he had turned the tables on Irish Swami. He'd never let anybody pull rank on him before.

Not even in the army, where he'd looked up all the books and got a colonel yanked. Christopher had charged him in front of the entire mess of refusing to advance with his leading companies when subjected to heavy decimating fire from M.G. 42's.

After that they had got a responsible colonel. Thirty!

Right. He didn't know how he'd do it. He only knew that he must. Christopher decided to give all his energy to the last ten buckets, which were going to be the worst. But suddenly they weren't. They were lighter. His muscles were co-coordinating. Some purpose was knitting inside him. The decision was made.

Something had to be done. This arrogant Irishman had these people under his thumb. People like this were just asking for it.

If you didn't stop them they went on and on. Christopher knew them all. He smelt them out. It didn't matter if it was a British gentleman coward or an Irish eccentric. They belonged to the same family of bullies. Christopher had suddenly got the sweep, and the spill of the bucket as he moved back from the well, in one continuous movement. It was an exhilarating discovery. He had also found his reason for being here.

After the bath Irish Swami continued his policy of appeasement. "You were beginning to get the hang of it at the end."

He nodded curtly and Christopher clamped down on the absurd gratification that followed this meagre palliative. He refused to let Irish Swami wash his shirt. He would do it himself.

The moment he started scrubbing at his shirt he regretted his gesture of independence. "Come here beside me," called Irish Swami loudly. "You're too near the well. The whole village has to use it, remember." He was still conciliatory, but the moment of reward was over. Christopher crawled back with the soap and his dripping shirt. He had been denounced again.

This was not the intention, but it got more embarrassing when Irish Swami patiently showed him how to beat the cloth. It was not to be flung down straight in front of you. The idea was to bring it in again as it came down so that the material crumpled up on the cement, producing maximum vibration and minimum shock. A few wallops like that could be more effective than a washing machine. Christopher watched the repeated sudden crumplings of the white cloth against the cement. The movement began to have an aesthetically hypnotic effect on him.

The big blond arm rotated without a stop, save for the moments it took for the cloth to pack itself together. Christopher saw it stop with that thrill of dismay reserved for the end of a perfect dance.

All he could manage was to thwack the shirt as near to his knees as possible and spatter himself with soap. "You're not trying to lambaste the cement, man. Bring it in. Bring it in as you come down. That's better," encouraged Irish Swami soothingly, but at the next attempt to pull it in smartly just before it hit the floor the shirtsleeves flew out, acting as parachutes. There was no impact, no sound at all. He turned the sleeves inside out, took the shirt by tail and neck and brought it down with such force that he heard a button crack.

A sliver of mother-of-pearl caught the sun in oyster glints as it skimmed away. "That's the trouble with shirts. Too many doodahs. Still, you're not doing too badly for the first time."

Christopher felt no glow. He didn't think he'd deserved it this time. He watched Irish Swami rinsing the shirt and his own white cotton cloths. He was watching everything now. He knew that tomorrow or the next day or the day after that, sooner or later, he would be forgiven nothing. His first job was to get the hang of all this. Until he had he would be in no position to give his attention to outsmarting Irish Swami. They hung the clothes on a line between two trees, then they both retired to sit in the shade.

Christopher counted. The men were indeed throwing forty buckets over themselves. Nudged by a new involvement he saw an altogether different scene on the raised cement podium. He now understood why the quadrangle of cement was so extensive, between fifteen and twenty yards square. There had to be plenty of room to stand well away from the edge of the well to protect the water. Then many people had not hung up their clothes hut spread them on the paving to bake.

What Christopher turned back to constantly was the movements, all the movements but specially those of the two people sluicing themselves carefully at the well. It was true. They poured the water measuringly, sparingly, as though they knew its value. Not a drop fell that had not first touched them. Also the own pounding their clothes. They all used the upward swing, the imperceptible tug back in. The thwack had a special sound. Some were more skilful than others and their note was clearer, sharper, but none as sharp as Irish Swami's. Christopher could find nobody else to swing him into that net of stillness.

He was aware of his own lack of skill, his utter inability to handle things, to fend for himself in a world where so little was ready made or even prepared beyond the initial stage. First that would apply to any Westerner and most rich Orientals, no doubt. Is that why this Irishman had chosen to live here?

"What made you decide to live like this?" The question was out before he could calculate its effect. Irish Swami was quick to answer him in the tone of his intention.

"Because if you want to understand the tradition you must live the tradition." Irish Swami made a circular movement with his outstretched arm. "This is port of it. You can't get it like this." He squinted, hunched down and pretended frantically to turn pages in a book. He was so good a mimic that

Christopher could feel the musty weight of the invisible volume under his hand. "Books are good. They've got it down. I write them myself. But if you want the efficacy of the tradition you've got to five it." He jabbed his finger towards the well itself, his own ashram in the next plot to the left, to another ashram a little way down which supplied him and the poor with food, to the cluster of huts beyond the grove, and, with a rainbow movement, to the big temple where pilgrims came, lastly, behind it, to the estuary where people made their temple ablutions.

"That's where you'll find it." Christopher witnessed for the first time one of Irish Swami's methods of finalising a discussion: a tremendous emphasis on one word in the last sentence, a slight turning away of the head and a lowering of the golden lashes to the cheek. Christopher's next question would have been about how Irish Swami had first come to the East. He was curious to know whether he had chosen to come or whether he too had been ejected.

Instead he waited until Irish Swami's head came round again. Why didn't people bring all their washing at one time? Dangerous as it was he could not help his questions.

"How many outfits do you think these people have? Sometimes one, two or three at the most. I've got two, but one's enough outside monsoon season. Most of the year one will do."

At lunch Irish Swami watched him eat. Hungry from the well exercise, he was intent on getting his rice and vegetable down rather than following the table protocol of the small ashram dining-hall. He disregarded the stares (Paul and Ramesh were looking). He hadn't come here to learn how to eat with his right hand and pick up his glass with the left.

"What am I doing wrong?" he asked, just to hear the sound of his unenthusiastic voice.

"Show him, Paul." Paul, a slim, gentle, timid Tamil boy who was usually treated with affectionate contempt, demonstrated that you did not twist your food around in your hand but picked it straight up with the fingers. You didn't mess all the vegetables and dhal and rice together. You left it as much as possible in the pattern in which Irish Swami had served it on your leaf-plate-a mound of white rice in the centre and five different types of curried side dishes around it. You were not just stuffing your face. You were the divine offering the divine to the Divine.

Christopher looked. The other leaf-plates did retain order and symmetrical arrangement, while his own was a shambles. He had wolfed his food. The others ate deliberately.

"I'm used to eating with a fork." He didn't try too hard to keep the wryness from his voice. Irish Swami let it pass.

"You'll get the hang of it. Take a few days, that's all."

Download this chapter as a PDF file

continued in Earthman Chapter Three

| Living Heritage Trust ©2021 All Rights Reserved |